I read That Obsessive Recursiveness: An Interview With Leo Mandel (conducted by Seth Dickinson) on my morning commute last year. It was perhaps the online article I most loved reading in 2017. At one point in the exchange, something strange happened in my chest—a warm dawning light, some lovely instability, the very sense of recognition Leo Mandel names as fanfiction's particular magic:

SD: Another writer taught me that fanfiction often explores narrative spaces that conventional work skips over. The practicalities of domestic life. Consequences of small actions. Recovery after trauma [...]

What do you think is important about fan work in the artistic, technical sense? The sense of "what can this do for me that a conventional novel cannot?" Why do people turn to fanfiction to fill in the margins and lacunae of a story?

LM: Um um um um. I left this for last and now it's super late where I am but I can think of two things true for me (omitting things I know people do seek out in fandom that I don't understand or enjoy personally): (1) a finer mesh, in mathematical terms, of emotional subtlety—like, I just read a well-reviewed novel that was supposed to be about this complex relationship and it was surreally boring, posed dolls, not a single move I didn't see coming. That attraction/repulsion thing with vulnerability again, I can mark out an author who came from fandom a mile away. Weight in small gestures, terror, gentleness. Fandom has made me feel less alone, a hundred times, via the delayed, reflected, ghost-trace intimacy of "someone else is moved or disquieted by this hair-thin vein of pathos; someone else notices this nuance, which I thought no one else detected; somewhere out there in this world moves an intelligence like mine." (2) queerness! [...] Fandom was the first queer space in my life; it's still the main, really the only queer space in my life. Obviously there are vast amounts of het work and plenty of homophobia in fandom also, but fandom as a whole feels queer to me in a particular "defiant, joyous, off-label use & doing it better" sort of way. So, commonalities—I think "subtleties in unusual experience" would be the theme, attention given to those subtleties, exactly as you suggested.

What a thing I did not know I needed. To have someone describe fanfic, its power and its charge, in this way. With dignity and poetry and reverence. Because yes, fanfic sings in pauses left by traditional narrative beats. But you do realize, don't you—that by filling in those spaces, fanfic deems them vital.

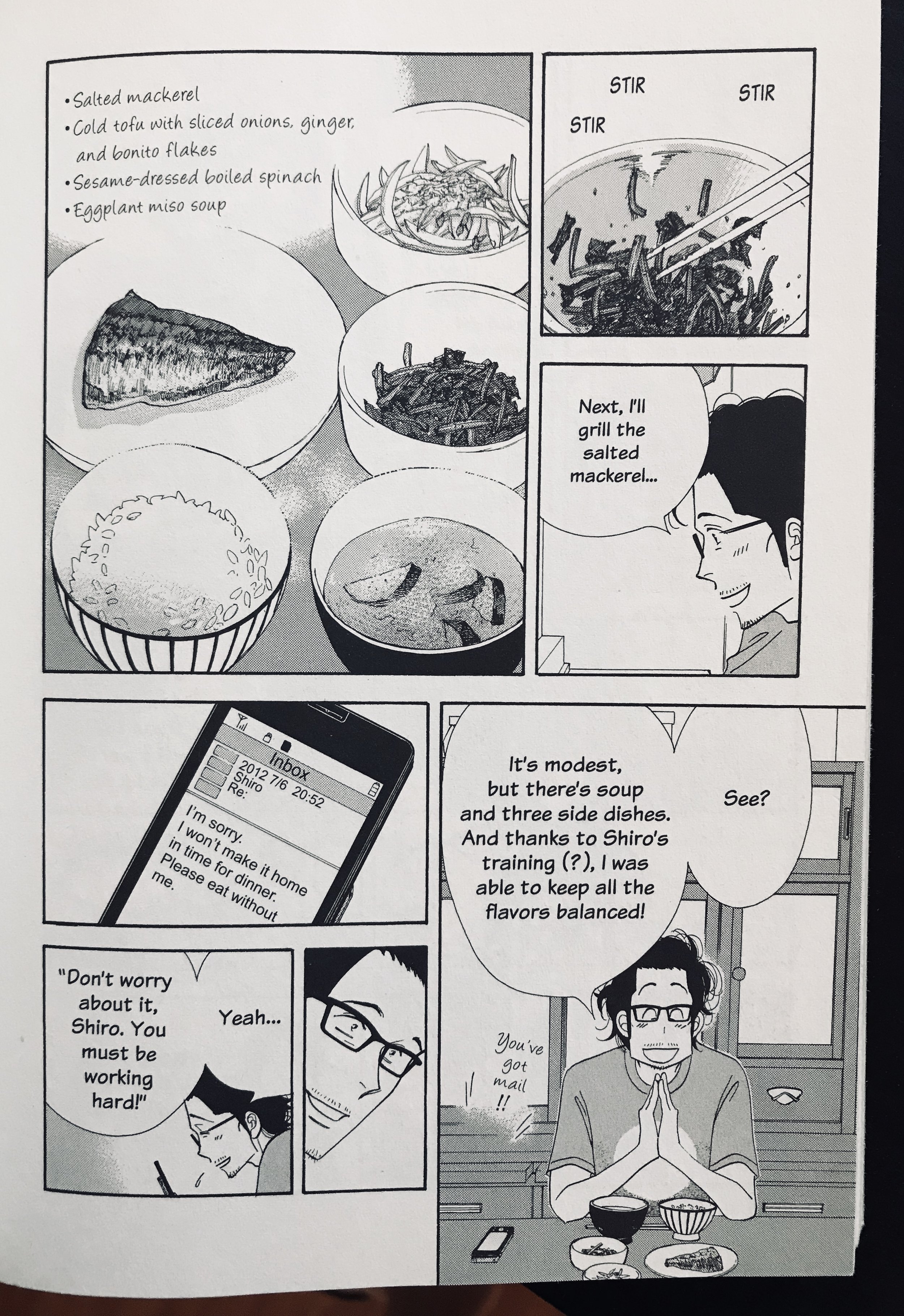

I just finished What Did You Eat Yesterday, Volume 7 by Fumi Yoshinaga. It's a slice-of-life cooking (!) manga featuring a gay couple in Japan. I smiled to myself many times while reading it, and I am not one who smiles easily.

Whenever food, which lines the rhythms of every person's day, comes up in stories, I find myself enormously pleased. Food is a comforting thing, of course it is, but it's also an effective driver of narrative, in a way that I'm surprised by now that I'm articulating it.

The Privilege of the Sword by Ellen Kushner features swordfights and intrigue and courtesans and murder, but I was awed by the chapter where 16-year-old Katherine is whisked off to train with master swordsman Richard St. Vier, who long ago withdrew from society. They live for some time in the countryside together, Richard teaching Katherine. In the process of learning the sword—and talking and eating and meandering through the estate grounds—they develop a shared intimacy, an ineffable bond.

The events of Chapter III of this section are so small. And so profound. Not because they rend the plot, but because the narrative eye makes them so. It is, simply, life. Good food, good company, a world ripe for observation:

There was always enough butter and cream and cheese, since there were more than enough cows. And suddenly, as the night air turned cold and the day sky burned a bright and gallant blue, the world was full of apples. The air smelt of them, sharp and crisp, then underlaid with the sweet rot of groundfall. One day the orchard was infested with children, filling their baskets with them for cider. The next week, pigs were rootling for what was left.

On one of the last warmish nights of autumn we sat by the stream, grilling trout stuffed with fennel over a fire of apple wood. The stars were thick as spilled salt above us.

He pulled his cloak around him and poked the fire with his staff. "There were apple trees where I grew up. I used to collect fallen wood for my mother. And steal the lord's apples, with his sons."

"Were you caught?"

"Chased, not caught. [...]"

I'm now reading Elif Batuman's The Idiot, and it shares this belief in the grandiosity of the mundane. The book's humor draws from enlarging the trivial. But it's a tender, loving effort:

I was supposed to make the dessert, a raspberry angel food cake with raspberry amaretto sauce. I had never made an angel food cake before, and got really excited when it started to rise, but then I opened the oven too soon and it fell down in the middle, like a collapsing civilization.

Because sometimes baking failures feel tantamount to disaster on a humanitarian scale, goddammit.

When a story holds joy, delight, strangeness, or funniness to the light, it tells us that lives that seem remarkably different—the king's and the pauper's, the savant's and the caretaker's—are fundamentally similar. It tells us circumstances within these lives may change—the empress' life before versus after ascension—but one moment is no less important than the next. It tells us moments are forever shifting—between the activist's serene, solitary morning and her striding bold before her people, ready to alter the shape of the world. It tells us the person at the center of a life may change, but her vitality will not.

Illuminating these facets of life is a way to value life itself. Because a majority of life is trivial, in-between, interstitial. Brushing your teeth, walking to the train station, scraping up the last rivulets of ice cream, adjusting your squeaking office chair, pausing at the grocery store because your favorite Top 40s song has just come on. Why shouldn't we celebrate all that in art? Why do we need calamity and war and the threat of a razed world, or triumph in the ring, or happily ever after with cake and a thousand spectators?

So yes. I think slice-of-life is important. I think fanfic does crucial work. I think comedy is serious stuff, and thus prefer banter over intoned prophecy. I don't want to watch our heroes wage an epic, bloody battle; I want to watch them watch their glories re-enacted by a theatre troupe who gets approximately 80% wrong, to hilarious effect. I like domesticity and mundanity, as performed by exceptional characters who are revealed to have foibles, who are revealed to feel as petulant and inelegant as we all do sometimes.

I thought, as an artist, I needed to write about solemn emotions, inscrutable narrators, heartbreak and estrangement, quilt-work historical plots. I still might—I am stuffed full of multitudes, and all that. But this, dwelling in the small and unspoken, is the stuff that enlivens me. So whatever I write next will be 90% trivial, and 100% serious.